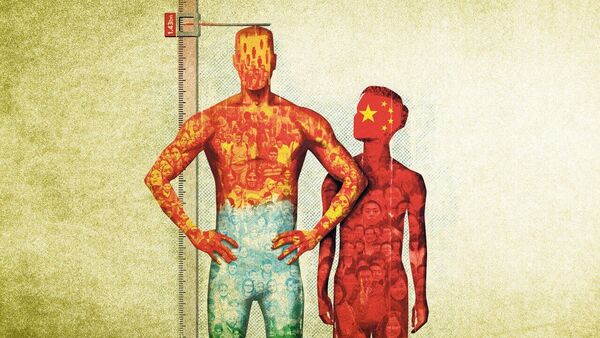

On 1 July, this is expected to change with India becoming the world’s most populous country—the population will touch 1,428.6 million. The Chinese population is estimated at 1,425.7 million. Other estimates suggest that China’s population is still greater than that of India. But even these projections state that India’s population will overtake that of China soon.

So, sticking to the UN projection, let’s take a look at chart 1, which plots the Indian and the Chinese population. In fact, there was a considerable gap between the population of the two countries almost up until the early 1990s. The rate at which the Chinese population rose has slowed down since the mid 1990s and from 2023 onwards, it is expected to contract. The same hasn’t happened with India.

In this piece, we will explain how the Indian population ended up overtaking that of China; why it may not be as much of a reason to worry as many people seem to be thinking, and finally, what it means for both India and China.

Babies per woman

Technically, babies per woman is referred to as the total fertility rate or the number of children born per woman during the child bearing years. “The most obvious physical constraint on this is the length of the fertile period (from menarche to menopause). The age of first menstruation has been decreasing from about 17 years in pre-industrial societies to less than 13 years in today’s Western world, while the average onset of menopause has advanced slightly, to just above 50,” Vaclav Smil writes in Numbers Don’t Lie.

Take a look at chart 2, which plots the babies per woman metric for both India and China.

Up until the 1960s, the average Chinese woman was having more children than the average Indian woman. Nonetheless, back then, both Indian and Chinese couples were having a lot of children because of the extreme poverty that both the countries faced. Take the year 1970. Data from the World Bank suggests that the Chinese per capita income stood at $113.2 (GDP per capita current US dollars). The Indian per capita income was at a very similar $112. In 1970, the babies per woman metric for India stood at 5.62 whereas that of China stood at 6.09. Hence, on average, 100 Indian women had 562 children. The same number for China stood at 609.

As Hans Rosling, Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Rönnlund write in Factfulness: “Parents in extreme poverty need many children… [Not just] for child labour but also to have extra children in case some children die.” Further, as Charlie Robertson writes in The Time-Travelling Economist: “When families have lots of children, the children become the parents’ “savings”. By the time they become teenagers [they] are hopefully earning an income… Eventually, they become your pension and can provide housing when you’re old.” So, when families are poor, they look at children as future savings.

The question is how did things change for China so quickly.

One-child policy?

In drawing room and social media talk in India, it is widely believed that China was able to control its population growth through its one-child policy enforced since 1980. As a recent news report in The Economist points out, this policy “allowed most Han Chinese couples a single baby (the rules were slightly more relaxed for ethnic minorities).”

At the same time, this policy was largely implemented in urban areas. It is said that it allowed China to ensure that women had fewer babies and so, the population growth slowed down. The problem is that the data does not bear this out, at least not totally.

Let’s consider the year 1979, a year before the one-child policy came into being. The babies per woman metric for China stood at 2.75, down from 6.09 in 1970. So, clearly, even before the policy became the norm, Chinese women were having fewer babies. What explains this? Now, take a look at chart 3, which plots the infant mortality rate or the number of infant deaths for 1,000 live births of children under one year of age.

In 1960, the infant mortality rate in China was 197.5. In India it was 158.2. By 1970, the figure for China had fallen majorly to 78. For India it had fallen marginally to 141.7. In 1979, the Chinese infant mortality rate was at 48.9 and that of India was at 118.4. So, basically, fewer Chinese babies were dying before the age of one.

“Once parents see children survive… both the men and the women instead start dreaming of having fewer, well-educated children,” the authors of Factfulness point out.

The couples have fewer children because women get better educated. “The data shows that half the increase in child survival in the world happens because the mothers can read and write.” This leads to “educated mothers [deciding] to have fewer children and more children survive” and “more energy and time is invested in each child’s education.”

This is precisely what happened in China. Data from a research paper titled Women’s Education in China: Past and Present, authored by Yujing Lu and Wei Du, points out that in 1950, only 10% of Chinese women were literate. This had increased to 51.4% by 1980, the year in which the one-child policy came into being. Compare this to India where the female literacy rate at independence was 9%. In 1981, it was 24.8%. This explains why by 1980, the babies per woman fell much more sharply in China than India. In 1979, the babies per woman in China was 2.75 against 4.81 in India.

The larger point here is that the fall in babies per woman metric eventually slows down population growth and this was already falling in China even before the one-child policy came into play.

The 4-2-1 phenomenon

In 1989, a Hindi movie called Ram Lakhan released. The actor, Anil Kapoor, played a character named Lakhan. And he sings a song where the words, for some random reason as is often the case in Hindi cinema, go: “one two ka four, four two ka one, my name is Lakhan”. Clearly, there isn’t any meaning to the phrase four two ka one here. But the same cannot be said about the Chinese phenomenon of 4-2-1, which is a clear outcome of the one-child policy, which the country followed from 1980 to 2015.

The babies per women metric continued to fall post the policy and in 1991 it was at 1.93, below the replacement rate of 2.1. As Smil writes: “The replacement level of fertility is that which maintains a population at a stable level. It is about 2.1, with the additional fraction needed to make up for girls who will not survive into fertile age.”

This implies that if on average 100 women have 210 children and this continues, the population will eventually stabilize. The Chinese fertility rate has continued to fall and is expected to be at 1.19 in 2023. This means that largely most couples have only one child and that one child, once she or he grows up, will be responsible for his two parents and four grandparents. This is the 4-2-1 phenomenon and it’s already having its share of impact.

The Chinese population is expected to shrink from 2023 onwards. In fact, the working age population, or the proportion of population aged 15 to 64, has already been shrinking for close to more than a decade. This can be seen in chart 4.

The median age of a Chinese is expected to be 39 in 2023. This means that China is rapidly ageing as its working age population and its overall population shrinks. As The Economist puts it: “Its over-65-year-olds will outnumber under-25s within about 15 years.” When it comes to India, the working age population is still growing. The median age is at 28.2 and the population is expected to start to shrink only from 2065 onwards. In the Indian case, over-65-year-olds will outnumber under-25s only in around 60 years.

All this will have an impact on future economic growth.

As Ruchir Sharma writes in The 10 Rules of Successful Nations: “If more workers are entering the labour force, they boost the economy’s potential to grow, while fewer will diminish that potential… If a country’s working-age population growth rate is not above 2%, the country is not likely to enjoy a long economic boom.”

The reason behind this is straightforward. As the younger lot enters the workforce, finds jobs, earns money and spends it, this drives consumer demand. When these individuals spend money, someone else earns that money. Over a period of time, increased demand leads to entrepreneurs launching new ventures, which creates more jobs, fuels more demand and so, the virtuous cycle works.

China has done a fantastic job of driving economic growth over the years, pulling millions out of poverty. Nonetheless, it is still a middle-income country. Its per-capita income (constant 2015 US $) in 2021 was $11,188. With its 4-2-1 population structure being the way it is, in theory, there is a chance of China getting stuck in the middle-income trap as its economic growth slows down in the years to come as the working-age population and overall population continue to contract.

India still has some opportunity on this front and it needs that opportunity given that its per capita income in 2021 was at $1,937. The median age of the population is still around a decade younger than China. Also, the working age population will continue to remain lower than the older lot for a while.

Further, while the Indian fertility rate in 2023 is at 2, which is lower than the replacement rate of 2.1, the population will not immediately start to shrink because of the population momentum effect or the fact that the number of women who will keep entering the fertile age will grow given the higher total fertility rate in the past. These women will have more children leading to the population continuing to go up for a few decades more. Eventually, the number of women entering the fertile age will start to come down leading to the population contracting.

In short, India still has an opportunity to cash in on its demographic dividend. But to do that, the youth need to be skilled and enough jobs need to be created, something that may not be happening currently.

Vivek Kaul is the author of Bad Money.

Download The Mint News App to get Daily Market Updates & Live Business News.

More

Less

#India #China #problem