At its most basic, a tariff is a tax or duty on an imported good or service. It can be on a single product, a category of products or applied on all imports from a specific country. In the first weeks of the new Trump administration, all these forms have been announced.

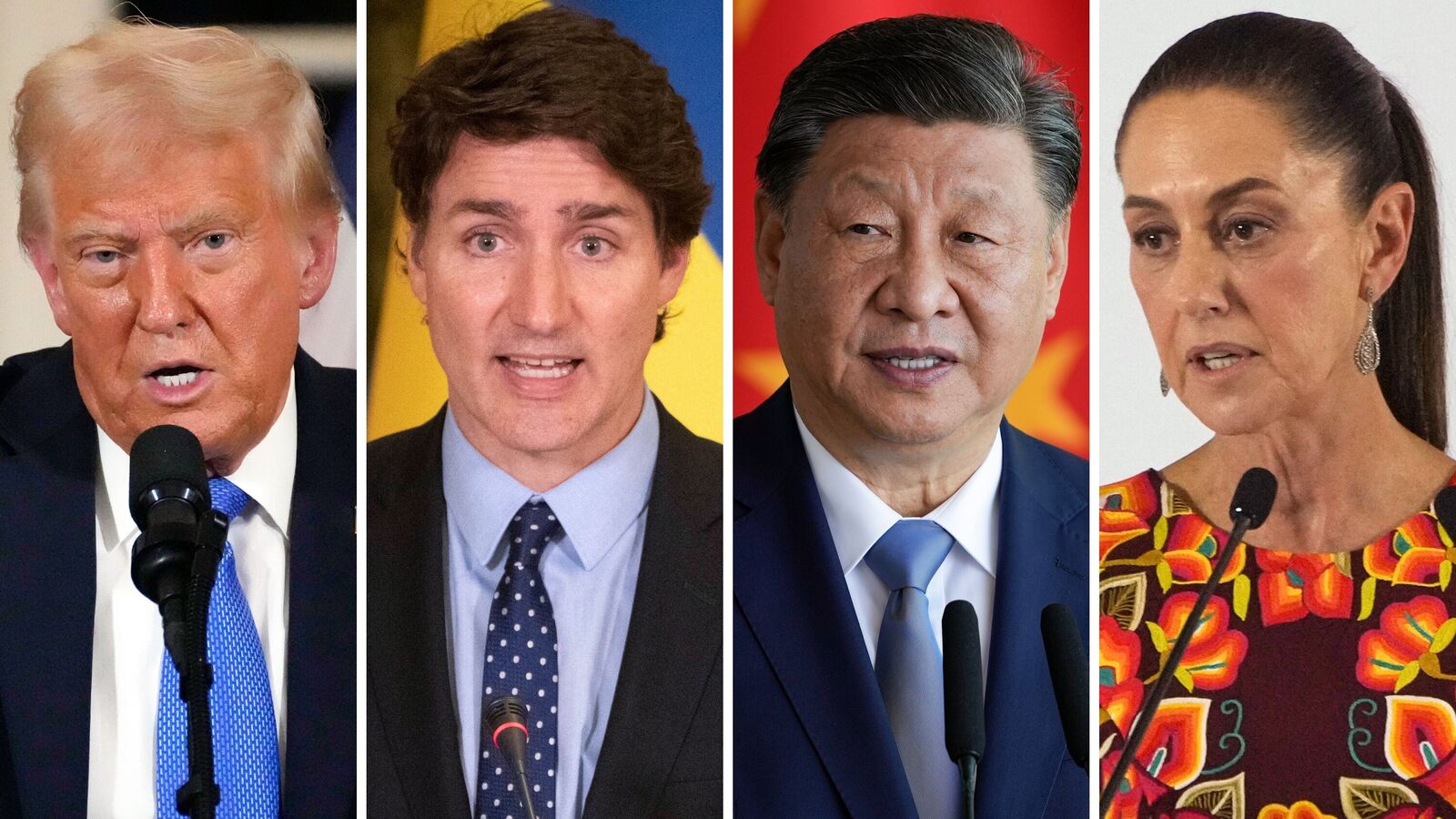

For instance, Trump’s 10%+10% tariff imposed on all imports that are products of China or Hong Kong. A 25% ad valorem tariff was to be applied on goods from Canada and Mexico earlier this month, but since then, several categories of products covered under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) have been exempted. Early in April, a bunch of reciprocal tariffs are scheduled to kick in, which will directly impact countries like India.

Also Read: Trump tariffs: Is the US president doomed to repeat history?

Nearly every country in the world imposes some tariffs. Import duties do serve an economic purpose. For example, Bahamas imposes an average 19% tariff on all imported goods, which contributes 60% of its national revenue base. Prior to the 16th Amendment of the US, promulgated in 1913, a significant portion of US federal income was raised from tariffs (income taxation was not permitted).

In addition to revenue, tariffs serve the purpose of sheltering or protecting domestic industry. The US steel and aluminium industries have long sought some form of tariff protection to combat what they claim are unfair trade practices.

Beyond economics, tariffs can be used as a negotiating instrument and a way to change behaviour. President Trump recently strong-armed the President of Colombia into accepting the return of illegal Colombian immigrants to the US with the threat of high tariffs on Colombian goods.

Also Read: China could be the beneficiary of Trump’s arm-twisting of Colombia and others

If those are advantages, then why do countries not have higher tariffs on more goods? That’s because in an inter-dependent world, higher tariffs attract retaliatory levies and in an overall sense restrict trade among nations. This defeats the Ricardian principle of comparative advantage among nations, thereby making goods much more expensive everywhere.

The ‘almost fully free-trade world’ of the last 40-50 years functioned reasonably well with low levels of tariffs across the board. Trump came to the White House having cut his formative business teeth during the dominance of Japan’s economy in the 1970s and 80s.

This seems to have shaped his views against other countries using industrial policies and subsidies that resulted, as he has argued, in large trade deficits for the US, which he considers a sign of economic weakness.

Alas, this understanding of the US position is both incomplete and obsolete. Global supply chains and the structure of the US economy have changed materially.

US auto parts go back and forth several times between the US, Canada and Mexico, before ending up as a finished product in the US. Imposing tariffs on Mexico and Canada would, by some estimates, increase the final cost of an ‘American-made’ car by about 25% because of the number of times automobile components cross borders.

Similarly, electronic goods cross borders in Asia many times before they are shipped to the US. In recent years, many so called ‘Chinese’ manufacturers have moved their final base to another country like Vietnam or Malaysia, thus defeating the idea of country-focused tariffs.

Also Read: India must keep its strategic options open as Trump’s tariffs kick in

There is also an esoteric reason why the US can only eliminate its trade deficit at its own peril. Since the dollar is the reserve currency of the world, the principal way in which the world is supplied with dollars is that the world imports goods to the US and secures dollars in return. If the US were to run a trade surplus, dollar liquidity in the world would shrink, which would turn out to be counter-productive to the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency.

Should the dollar’s status as the reserve currency come under serious threat, US bond markets would likely experience a significant decline, especially given the current context of the US operating with a fiscal deficit amounting to 125% of GDP (and growing).

Paradoxically, the US should be the last country in the world to impose tariffs, even if other countries have such import barriers. The Trump tariff era is therefore a dangerous and ill-informed experiment. If it ends up being implemented, it will prove to be very costly for Americans.

Also Read: Madan Sabnavis: There is no alternative to the US dollar as the world’s anchor currency

For other countries, the outcome of the US’s new trade policy will depend on which type of tariff the country is subject to. China, for instance, would be best off focusing on efficiency and productivity improvements in such a way that the impact of America’s 20% tariff is mitigated.

Engaging in a trade war by imposing tariffs on imported pork and the like from the US, however, makes for good politics but bad economics for Chinese citizens. Countries like India that are potentially subject to ‘reciprocal’ tariffs should blame Americans politically, but use the opportunity to reduce their own tariffs. This would benefit India’s trade with the US. For Canada and Mexico, though, the policy shift is an existential threat, as there are very few options available to them other than hoping that domestic lobbies in the US will force the Trump administration’s hand against these irrational tariffs.

P.S: “The harm which a tariff does is invisible. It’s spread widely,” said economist Milton Friedman.

The author is chairman, InKlude Labs. Read Narayan’s Mint columns at www.livemint.com/avisiblehand

#Trade #war #brace #return #beggar #thy #neighbour #policies