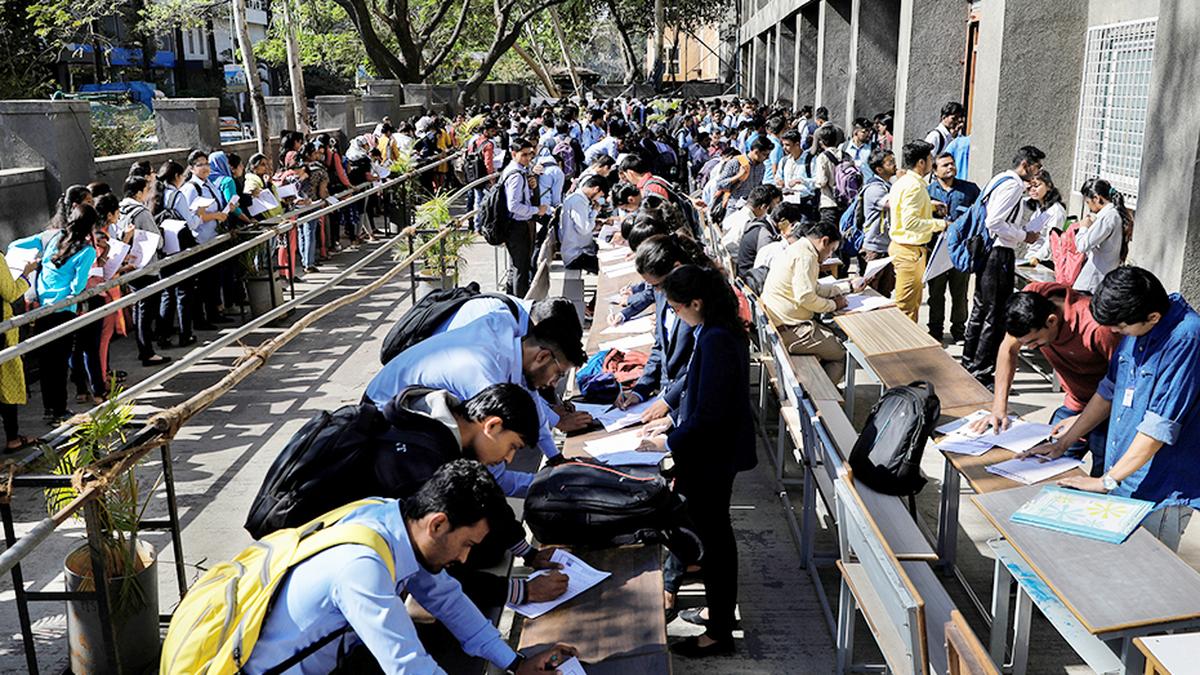

Shivam Rangire, 24, is among the almost 20,000 candidates who turned up on July 16 at Air India Airport Services Ltd.’s (AIASL’s) gate at Andheri in Mumbai for a walk-in interview being held to fill 2,216 vacancies for the post of handymen.

The overcrowding could have led to a stampede. On receiving an email earlier in July, he was excited and hopeful of securing this job. He travelled from his hometown Akot, near Akola, about 600 km from Mumbai, in a bus only to be shocked on reaching the venue as he found the number of job aspirants overwhelmingly outnumbered the positions offered by AIASL. Following instructions, he returned home and again journeyed to Akola for a test to be held on July 30 by AIASL.

“We could have handled the crowd better” said Rambabu Chintalacheruvu, Chief Executive Officer , AIASL. “Normally, when interviews for handymen happen, a large turnout happens,” Mr. Chintalachheruvu added. He said the local police were informed regarding the crowd in addition to providing facilities such as tents and water for the candidates.

A handyman or loader is responsible for shifting luggage from passenger and cargo aircraft at the airport. A candidate is expected to have graduated class 10, according to a recruitment notice on AIASL’s website. A Bachelor of Arts (BA) graduate, Mr. Rangire had to wait for two years before applying for a job he was grossly overqualified for. The recruitment process involved a physical fitness test, which is measured by the number of up to 20 kg each gunny bags one can toss within 30 seconds. Those clearing seven bags in 30 seconds qualify for the next round, said another job seeker, who like Mr. Rangire is part of Maharashtra’s labour force.

The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) of India 2023-24 data has a slightly dull picture of Maharashtra compared with the national average. While both labour force and workforce participation rates have increased by about 2 percentage points for India, the same metrics have seen a marginal dip compared with 2022-23 for the State. Labour force participation rate is the share of the workforce that is employed or currently looking for employment. The PLFS 2023-24 estimates the State’s urban unemployment to be at 5.2%, against 4.6% in the previous year. With respect to overall unemployment rate, Maharashtra clocked 3.3% in 2023-24, more or less the same as the national unemployment rate of 3.2% for the same period.

Economists believe the data does not reflect the complete picture of the employment situation in India. “Millions (of) so-called employed in PLFS are unemployed as per CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy) and ILO (International Labour Organisation),” Santosh Mehrotra, Visiting Professor, Centre for Development Studies, University of Bath, told The Hindu. For instance, unpaid family labour is considered as employment in PLFS but not so by the CMIE or the ILO, Mr. Mehrotra added. Moreover, national trends suggest an rise in agricultural sector employment and decrease in manufacturing employment, which will not show up as a dip in employment numbers, he said.

This becomes clearer when looking at data from India Unemployment Report 2023 from the ILO. The global labour body suggests educated unemployment in Maharashtra was 15% in 2022, an increase from 11% a decade ago. PLFS, however, shows the level of unemployment of those educated above secondary level to be at 5.9% in 2023-24 from 6.1% in the previous year. To be sure, PLFS report gives data for all working age groups, while ILO report shows data only for labour in the age group of 15-29.

‘Failure of employment generation’

Apart from direct unemployment, there is also the problem of being unemployable or employed below one’s qualification. Mr. Rangire’s story is a case in point. The government in Union Budget 2024-25 mentioned skilling youngsters and providing internships in top companies. Education experts believe this is more a problem of the education system and is an act of shifting the blame on to students. “The failure is not of the student. They studied what they were told to study,” Maheshwar Peri, Chairman of Careers 360, a career counselling portal, told The Hindu. “Our failure of not creating enough employment opportunities is being transferred to the employability of the students”, said Mr. Peri. There is a gap between what the students are trained for, what they are promised and the real employment-generation capacity of the system, he added. “There is a crisis in the employment-education fit,” Mr. Mehrotra added.

While Mr. Rangire was able to find a vacancy in a government-controlled entity in hope of a job, others struggled. If he remains unemployed, for now, he qualifies to get ₹10,000 monthly under the recently announced Ladka Bhau (Adorable Brother) Scheme by the Maharashtra government. This initiative aims at providing young men with a monthly stipend based on educational qualifications, in the range of ₹6,000 to ₹10,000, and practical work experience.

Irrespective of the educational qualification, Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGA) provides up to 100 days of labour opportunities annually. Maharashtra’s Economic Survey 2023-24 showed that households provided with jobs increased to 24.5 lakh in 2023-24 from 20.4 lakh in 2021-22. On an average, a household was employed for 47 days in 2023-24 up from 41 days in 2021-22. The increase in MGNREGA employment is a reflection of increasing rural distress.

Proliferation of informal jobs

“There are many who are over-qualified, some with Master of Business Administration degrees and even with PhDs, but you will find them driving autorickshaw or cabs, selling tea or snacks in cities,” said Vivek Monteiro, Secretary Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) Maharashtra State Committee. Some people who have vocational skills take up work as carpenters or painters. The rest have to depend on ‘naka’ and ‘bandkham’ work [casual labourers and construction workers]. “The cab and auto drivers are large areas of self-employment which are indications of under-employment,” Mr. Monteiro added.

Agricultural distress is also a reason behind people moving to casual labour. “Farmers’ children are unable to sustain the agribusiness due to failed government schemes and insurance covers. They move to Mumbai to look for odd jobs,” said Sachin Atmaram Holkar, an agriculturist based in Nashik. Export curbs on onions, intended to arrest inflation, pushed farmers to a livelihood crisis in rural Maharashtra. These farmers migrate to Mumbai for daily wage labour, which are jobs that have no security, Mr. Holkar added.

Some like Amol Ashok Gorde from Nashik, stayed jobless for eight years. Mr. Gorde appeared for 50 public exams, spending about ₹2,500 on each of them and doing odd jobs, all despite being an engineering graduate before settling down in a job at a private firm as an assistant engineer. Mr. Rangire and Mr. Gorde, from Maharashtra’s interiors, are among countless people with similar story across the State.

Government action

After a Cabinet meeting on July 30, Maharashtra’s Chief Minister Eknath Shinde announced projects worth ₹81,000 crore, which, he said, would employ 20,000 people. The projects would be focussed on sectors like semiconductors, green energy and lithium batteries. The projects are expected to come up in Vidarbha and Marathwada regions, but the timeline on employment generation is unclear.

Until then, the educated and skilled youth look forward to Deputy Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis’ assurance that the government would fill up one lakh vacant government jobs.

Significantly, the announcement was made months ahead of the Assembly elections, perhaps an indication of the importance employment is likely to be during the State elections.

Published – October 06, 2024 06:00 am IST

#Maharashtra #projects #galore #dent #unemployment