That is how his novel One Hundred Years of Solitude begins. The line merges three periods of time in a single sentence. The narrator talks to us from the present, conveys that he will be executed in a distant future (he is not), and sets up the distant past of his father, where the novel properly begins. I wish I could say that this is why the sentence is memorable.

Or, because a little boy’s discovery of ice is a beautiful surprise in such a grave sentence. But I am sorry. I believe the line has become famous because that’s how far many people have gone with the book. More or less. No doubt, an unknowable multitude have read it fully in many languages, but it is also one of those books that more people revere than have actually read.

Now that Netflix has adapted it as a series, about 100 million people can get to know the classic, including film critics perhaps. And, even though they may like most of what they see, they may also wonder what the fuss over the novel was all about.

Like some classics, One Hundred Years of Solitude is actually a very good novel. Other aspects of its greatness come from the lottery of fame. Why some good novels are better known than other good novels is part of the absurd magic of luck.

Since hype is how good things come to us, the collective subconscious of people tolerates hype and a monopoly over creating it. Novels like this have let the Western literary establishment, which tells us what to read, survive. Yet, intellectuals often get it completely wrong.

The novel is framed as “magic realism,” which is a nonsensical term that takes itself too seriously, as though it has more gravitas than fantasy. Outside fairy tales, all magic in stories is magic realism, including stories in the Bible and Hindu epics. But that is not my quarrel. My quarrel is that the magic in the novel is not about fantasy at all.

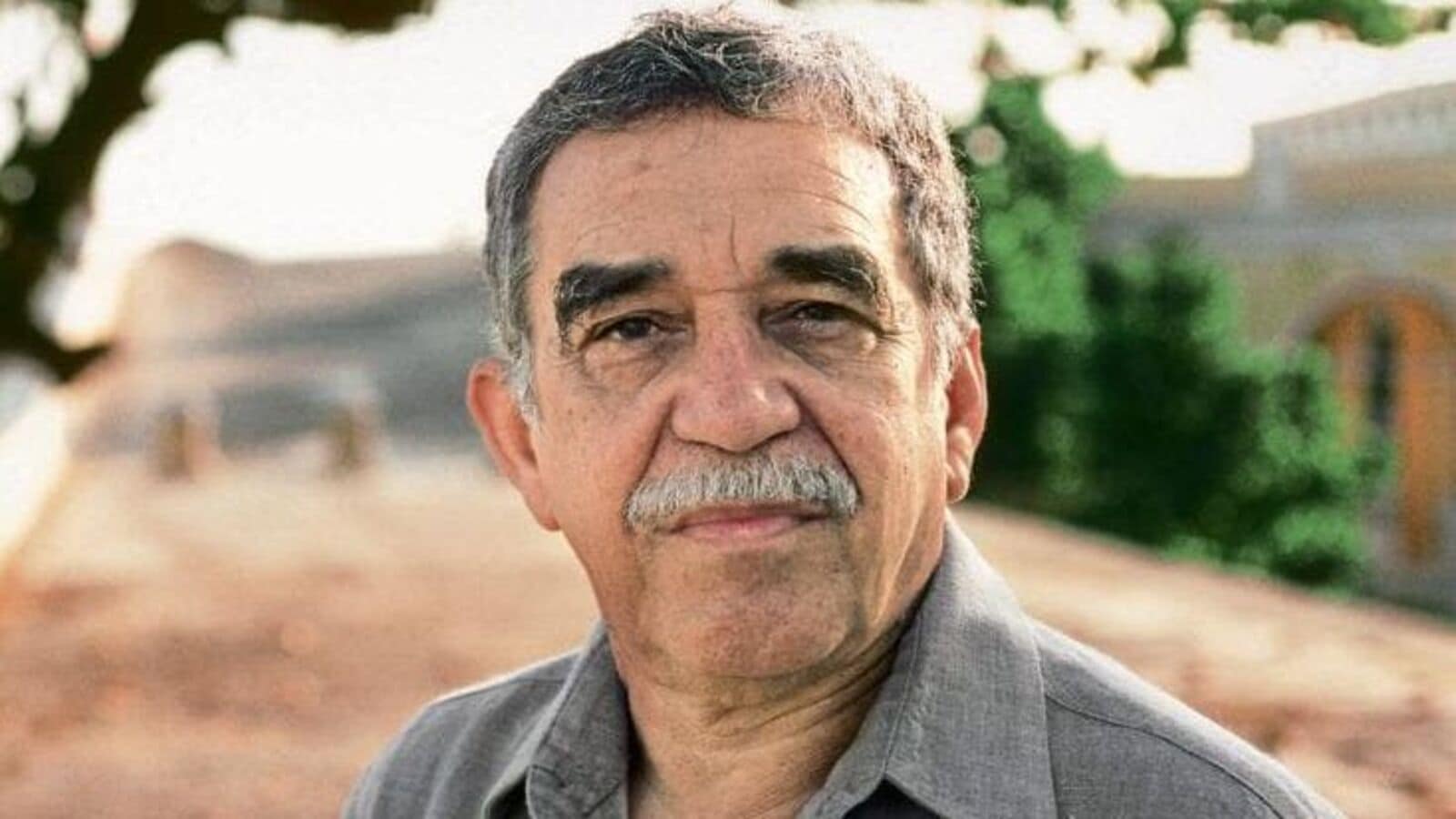

Strange things do happen in this family saga that spans a century in Macondo, a fictitious place. There are ghosts, and a person’s blood sets out to go somewhere. Garcia Marquez was trying to narrate how ancient people used to tell a story—by converting metaphors into descriptions and through mistaken views of natural phenomena as supernatural.

When you narrate your grandmom’s stories of what she saw and heard, without the condescension of interpretation, they may seem like magic.

Arthur Clarke once said, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This is true of ancient history, too. A historical account by a person in olden times will seem like magic. And this is what Garcia Marquez achieved as a story-telling technique.

A few years ago, it rained red all over Kerala. A vast region appeared to be soaked in blood. Science ruined the magic; it said a meteor had exploded over the region.

If this had happened in another time, people would have said it rained blood one day, they would’ve told that story in a way that would read like a page from One Hundred Years… That is an unspoken playful strand in the book. In fact, this is what it is largely about.

There is a moment in the novel when Macondo is struck by an insomnia plague, which causes inhabitants to forget the names of things.

A few years after its publication in 1975, neurologists formally recognized a form of dementia called semantic dementia, which is remarkably similar to Garcia Marquez’s portrayal. Such a disease must have afflicted a Columbian village long ago and Garcia Marquez must have heard of its tales.

Compared to our distant future, our distant past could be more astounding as magic. There is a lot that has vanished and we have no idea of the sort of things that used to exist. It is not just species that go extinct, but whole ways of human life. Some of that survives in our fables.

Surely, Garcia Marquez was not the first to use fables to tell history, because no one is ever the first in anything. Surely, it is overstated that he derived the technique from his Columbian heritage, for which culture did not tell history through fantasies, exaggerations and metaphors presented as reality? Even the West’s history has a bit of that.

Fantasy that never happened is somewhat lame. It is dull from an intellectual point of view. The power of Garcia Marquez, even when we do not know why we feel it, comes from plausibility.

Surely, he did make up some of what he wrote about and not everything was an exaggeration of metaphors and natural phenomena; even so, to call the book by a foolish term for fantasy is to deny people the actual fun of his work. And the novel is a lot of fun.

Also, generations of writers have ruined themselves trying to imitate this book thinking it is about inserting absurd magical things in the middle of a rational plot.

Garcia Marquez himself was not very pleased with the classification of his genre as magical realism. There is a beautiful line very early in One Hundred Years of Solitude, when he says that the world was so recent that things didn’t have names and you had to point.

And that was what happened with his own works. It was so new to the West at the time that the literary establishment had to invent a name. They would have been more articulate if they had just pointed.

#Manu #Joseph #Gabriel #García #Márquez #time #Netflix