Then we had to change vehicles. The next 10km could be braved only by a rugged low-cost off-roader with high chassis, with little that could be damaged by the narrow rocky path.

Even these tough four-wheelers couldn’t get beyond a point. Three bikes took us another 2km ahead, and then we walked for 15 minutes.

We spent the afternoon in the hamlet, listening to its inhabitants describe what they were doing to increase yields of their small farms, manage water better in their hilly terrain and plant mango orchards. The annual income of these families ranged from a high of ₹40,000 for a few to many with zero.

There was no mobile connectivity in that hamlet. You had to climb a hill a couple of kilometres away to get a faint signal. So, government schemes and entitlements, which required digital validation or transactions were either not available or hard to access.

The government primary school in the hamlet also served nearby habitations—an overall population of about 400; it had one teacher and 40 children. This teacher had taken a room on rent in a hut at ₹300 per month and was living there.

No one could remember the last time a teacher had worked in the school for more than a few months; each one of them figured out a way to get a transfer to another school somewhere else.

This teacher had been around for two years, making no effort to move out. The nearest private school was in a small town about 40km from the hamlet.

The closest private hospital was 60km away—in another small town. The government primary health centre (PHC), the country’s most basic facility, was about 25km from there, which would take 3-4 hours to reach. The nearest outreach centre of the PHC with a nurse was about 6km.

All of this through the very terrain that we had traversed to reach the hamlet. So, for example, if someone’s leg was broken, they had to go 25km to reach the PHC. First carried on foot, then on a bike, and then by means of some rugged vehicle if available.

If an illness required check-ups twice a week, it would never happen. Both the PHC and private hospital were staffed only up to 30-40% of the required level.

Thousands of such habitations dot India and a few hundred million people live in such places. They lead lives of remoteness—from almost everything that we identify with our sweeping tide of progress and development. Almost everyone is in poverty, no matter how it is measured, by income, consumption or ‘multidimensional’.

But no measure can convey the feeling or experience of poverty. Much that is taken for granted in the world today doesn’t even exist in the consciousness of people in this remoteness or are myths of distant lands brought by returning migrant labour. Just being there requires relentless effort. Inhabitants reaching out and outsiders reaching in involves a struggle.

Defined and frozen by remoteness is one of three types of poverty that I encountered in the past two weeks.

All types of poverty have some common features. The most obvious is our inability to create jobs and livelihoods that are just and fair and secure.

But there are sharp differences too, which then determine both the experience of poverty and the challenges that confront efforts to improve things—as in the impossibility of doing anything without first tackling remoteness in the first type of poverty.

The second type of poverty is usually within an hour or two from some airport, if one uses that privileged measure of distance. Most of these places have high population density, and little land and other natural resources per capita.

Schools, hospitals, courts, markets of various sorts, government offices, other basic institutions and services are not distant. Many of these are within or near habitations, and almost all within a driving distance of an hour or two.

Social mores and structures have a vice-like grip on everything here and are the most stark feature of this poverty. They permeate everything and determine almost all experience. Social and public institutions are firmly in this web and are largely dysfunctional.

If you are a woman, markets will be inaccessible, the mobile phone too, and your food will be family leftovers even when you need the most nutrition; your caste will shape your child’s experience in school, as well as your access to justice, places of worship and treatment in hospitals.

Community antipathies are often vicious, carrying the weight of centuries of strife. And then there is a lot more. Such poverty is an indivisible web of mores, structures and lack of economic resources. All of these must be confronted together to change poverty here.

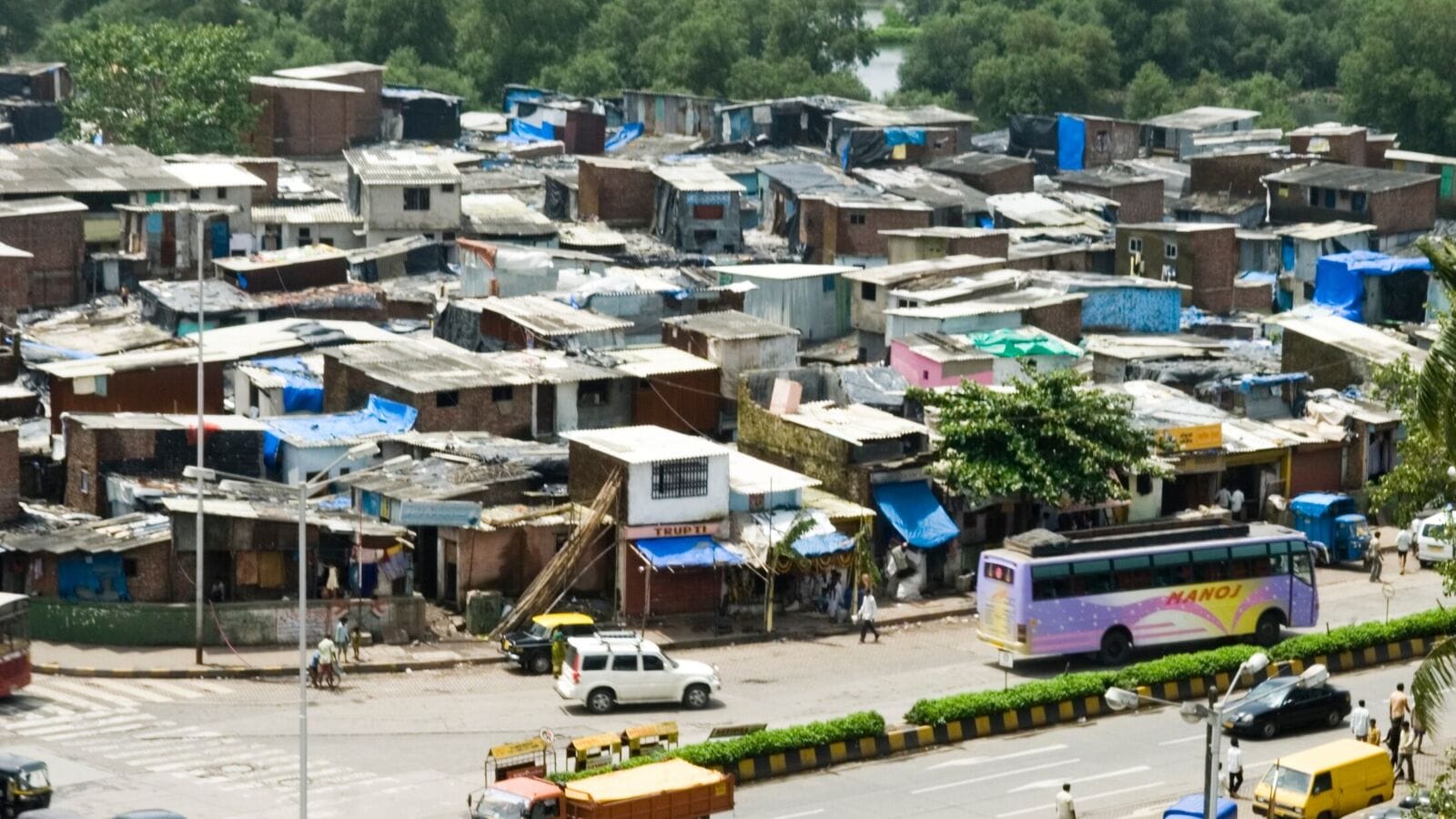

The third kind of poverty exists right next to you and me. Slums, shanties or blue-tarp tents, with their inhabitants cleaning or constructing buildings or working on a road.

For people in such poverty, everything—all of progress and development—is right there, yet hopelessly far. Across the deepest possible chasm—that of apathy.

Our actions and inactions—institutional or societal, as individuals or communities—are brazenly apathetic to millions of lives that surround us every moment. We could do everything but do nothing. They may live in poverty, but we are the country’s poor.

#types #poverty #traps #country